The role of women in the church, particularly in leadership roles, has been debated for centuries. There have been seasons in which women were found in numerous leadership roles in the church…and seasons in which women were largely prohibited. During the first six hundred years of Christianity, limited historical evidence witnesses to the fact that the ministry of women flourished but serious investigation reveals evidence that no uniform practice or policy regarding the admission of women to ministry prevailed during the early Christian centuries. During the next 1000+ years, women suffered numerous inequalities and discrimination, in society and in the church. The 19th century brought an increase of women in leadership and ministry, but that declined again in the 20th century. In the past hundred years, numerous scholarly books and articles have been written in support of women in leadership, as well as those written to respond to such claims.

Seeking to establish church practice, many have looked to both the Bible and our Church Fathers for standards. There is wisdom of basing our position on Biblical and historical precedent. But, there are questions that deserve at least some attention and consideration as we seek to apply that wisdom. Can we just read our Bibles at face value? Can we trust the conclusions of our Church Fathers on the issue of women in the church?

We often find ourselves wondering, “Why do I need to interpret the Bible? Why can’t I just read it at face value? Do I really need to understand the Greek and Hebrew to understand what God is saying to me?” When another interpretation is different than ours, and was gained through such study, we may question the integrity of the other. We are tempted to ask, “Are they simply trying to read into the Bible what they already believe? Why are they now seeing something that has never been seen in the pages of Scripture before?”

We can read our Bibles at face value and glean a lot from it. However, this doesn’t negate the need to interpret. It doesn’t release us from the need to study the original words if we seek to apply it more broadly than for our own personal edification. Sometimes we are tempted to think those who do are simply trying to get the Bible to say what they want it to say. This is especially true when their interpretation is different than what we’ve known all our lives. The nature of Scripture and the nature of the reader necessitate the task of interpretation.

“A more significant reason for the need to interpret lies in the nature of Scripture itself. Historically, the church has understood the nature of Scripture much the same as it has understood the person of Christ…the Bible is at the same time both human and divine. The Bible is the Word of God given in human words in history. It is this dual nature of the Bible that demands of us the task of interpretation. Because the Bible is God’s Word, it has eternal relevance; it speaks to all humankind, in every age and in every culture. Because it is God’s Word, we must listen and obey. But, because God chose to speak his Word through human words in history, every book in the Bible also has historical particularity; each document is conditioned by the language, time, and culture in which it was originally written(and in some cases also by the oral history it had before it was written down.) Interpretation of the Bible is demanded by the “tension” that exists between its eternal relevance and its historical particularity.”(1)

The Bible is an ancient piece of literature, written by a number of authors over a period of 1500 and was completed(the writing) almost 2000 years ago.. It is made of of various genres, each needing a different approach. Poetry cannot be taken as factual as history; prophecy is more symbolic than epistles. Just like any piece of literature, the Bible is filled with literary devices such as hyperbole and allegory as well cultural vernacular and idioms that we don’t readily understand as such. We don’t think twice about idioms in our culture that often create difficulty when speaking through a translator. This same difficulty is inherent in the reading of Scripture and often requires interpretation.

It is important for us to always remember that there is great need for humility as we seek to interpret, understand, and apply the Scriptures, and an intentional effort to avoid arrogant certainty. We cannot say with a large degree of certainty, “The Bible clearly says…” because it’s not always so clear.

Not only is interpretation not always clear, the translation process itself has inherent difficulties and provide another reason for the need to seek to understand the meaning behind original languages. First, there are about 5,000 Greek manuscripts from which our modern Bibles are translated and there are variances in all of them. Which variation is the correct one? For example, 1 Corinthians 14:34-36 is found at several different locations within chapter 14, depending on the text used. Which placement is correct? Does it belong after verse 33 as it is in some ancient texts? Or, after verse 40, as it is in others?

Second, there are about 5400 Greek words compared to over 170,000 English words. This means that a Greek word may carry many English equivalents. To determine the correct meaning, context is necessary. Think of the various ways we can use the English word “play.”

My children play outside everyday around 2pm.

I bought tickets for a Broadway play.

My daughter will often play tricks on friends.

I don’t want people playing me. But, when I’m joking around with someone, it’s ok if others play along with me.

There was a small glitter of sunshine that played upon the water.

It seems like there’s a little play in the steering of our vehicle.

It only took 4 plays for them to score a touchdown.

Context is necessary to ascertain the intended meaning of each usage of the word ‘play.’ We cannot just choose one or two definitions and apply it to all the usages. When translating Biblical passages, translators rely on extra-biblical occurrences to establish context.But, when words have very little context, it can be difficult to deduce an exact meaning. One example is the Greek word authentein. It’s only used once in the New Testament, never in the Septuagint, with only a handful of occurrences in extra biblical Greek texts, some of them are just fragments without the full context. Even with a small number of occurrences, there are a variety of possibilities of what authentein might mean, making it difficult to ascertain exactly what Paul was saying in 1 Timothy 2:12.

Because language changes over time, to render a good understanding of a word, its context must to be as close to the era in which the passage was written as is possible. It does little good to choose a meaning that didn’t exist when the passage was written. Tod ay, the word “awful” means something very bad or unpleasant, but centuries ago it meant something that inspired reverential wonder…awe-ful. I doubt Isaac Watts was describing God’s throne as bad or unpleasant when he penned the words, “Before Jehovah’s awful throne….”

In the early 18th century, after 35 years of work, Sir Christopher Wren completed St. Paul’s Cathedral in London and invited Queen Anne to inspect the building. Her judgment? “I find it awful, amusing, and artificial!” What an insult! Or…is it? Sir Christopher Wren was delighted with her judgment. In the early 18th century, “awful, amusing, and artificial” meant “awesome, amazing, and full of skill and artistry.” Only 300 years ago, and in the same language we speak, yet today’s reader would have a completely different understanding of Queen Anne’s words than those who heard them when they were first spoken.

With a variety of possibilities, limited context, and changing languages, it’s the job of translators to choose the best English word, and their choices affect how we understand what we read. We cannot discount the fact that translators bring their own presuppositions, ideas, beliefs, and convictions to the translation process. Translation is, to a large degree, interpretation. We cannot ignore this reality. Every translator is affected by the culture in which he/she lives and that influences how they translate or interpret the text. When we read our Bibles, the words chosen during the translation process have been influenced by a different culture and the presuppositions, ideas, beliefs, and convictions inherent to that culture.

For example, in the parable of the lost son, Luke writes that the father saw his son coming, had compassion on him, and ran to his son(Luke 15:20). The Greek word for run is “trecho,” and means to run(like an athlete competing in the ancient Olympic games). But for almost 2000 years, Arabic translators had great reluctance to render this verb as running. Instead a wide range of such phrases were employed…he went…present himself…hastened…so they could avoid the humiliating truth of the text…the father ran!(2) This was far too humiliating for a Middle Eastern translator to attribute a person who symbolizes God. They didn’t translated trecho as run until 1860 because their cultural beliefs affected their translation.

In the late 4th century, Jerome translated the Bible into the Latin Vulgate. Several modern translations, such as the KJV, NKJV, are translated from the Vulgate, though they use the Greek texts for some passages. When Jerome translated Romans 16:2, he chose a weaker Latin term to refer to Phoebe. The Greek uses the term ‘prostatis‘ which comes from a group of words that has a strong connotation of leadership and authority. It means “a woman who is set over others.” A secondary meaning is “female guardian, protector, patroness.” In the ancient Greek, this was term for women who were legal representatives of strangers, or legal guardians for minors. Both primary and secondary meanings of the 1st century Greek word ‘prostatis” had the connotation of leadership and one with authority to act on behalf of another. But, Jerome translated ‘prostatis‘ into the Latin ‘adstitit‘ which means “to stand near,” changing the connotation from one who is a leader to one who is a helper or an assistant. By the 4th century, women were being squeezed out of leadership roles, and the culture viewed women as weaker and inferior, incapable of leadership. This belief affected Jerome’s translation.

More recently, the 2016 version of the ESV translated Genesis 3:16b as “Your desire shall be contrary to your husband, but he shall rule over you.” In the original, there is no implication nor indication for the use of the word “contrary.” The original language uses the preposition “el,” meaning “to, towards, into.” The LXX uses the Greek preposition, “pros” which also has the meaning of “toward.” Nothing in the original implies that Eve’s desire will be contrary to her husband. Translators changed the preposition because of how they understood Eve’s punishment. Once again, the beliefs of those involved affected their translation.

Given that translators, theologians and others naturally bring their own cultural beliefs to the work of Bible translation and interpretation, let’s turn our attention to the cultural beliefs of our Church Fathers. When we look at church history, we see a strong bias against women, a culture that held presuppositions and beliefs that most likely affected how the Bible was translated, interpreted, understood, and applied.

“Woman, do you know that you are [each] an Eve? The sentence of God on this sex of yours lives in this age; the guilt must of necessity live too. YOU are the devil’s gateway; YOU are the unsealer of the forbidden tree; YOU are the first deserter of the divine law; YOU are she who persuaded him whom the devil was not valiant enough to attack; YOU destroyed so easily God’s image in man. On the account of YOUR desert–that is, death–even the Son of God had to die.” Tertullian, 160-220AD

“God maintained the order of each sex by dividing the business of life into two parts, and assigned the more necessary and beneficial aspects to the man and the less important, inferior matters to the woman.” And, “The woman taught once, and ruined all. On this account..let her not teach…the whole female race transgressed…Let her not, however, grieve. God hath given her no small consolation, that of childbearing.” John Chrystostom, 349-307AD

“Men should not sit and listen to a woman…even if she says admirable things, or even saintly things, that is of little consequence since they came from the mouth of a woman.” Origen, 184-253AD

“Out of respect to the congregation, a woman should not herself read the law. It is a shame for a woman to let her voice be heard among men. The voice of a woman is filthy nakedness.” Jewish Talmud

“What is the difference whether it is in a wife or a mother; it is still Eve the temptress that we must be aware of in any woman… I fail to see what use women can be to man, if one excludes the function of bearing children.” St. Augustine, 354-430AD

“As long as woman is for birth and children, she is different from man as body is from soul. But if she wishes to serve Christ more than the world, then she will cease to be a woman and will be called man.” Jerome, 347-420AD

The disdain ancient Jewish rabbis held for women influenced the version of the Old Testament we still rely on today, the Masoretic text. Twice, the church has lost an understanding of the language of Hebrew Bible. The first time was about 100 years before the time of Origen, which would’ve been shortly after the destruction of Jerusalem by Titus. The second time was during the Dark Ages. Rabbis were enlisted to teach the Hebrew language, but each time they taught more toward Talmudic ideals than Christian. These rabbis taught an inferiority of women. They held a view of women as not much more than meat “which one may eat, salt, roast, partially or wholly cooked.”(3) Rabbis believed it would be better for the Torah to be burned than to be spoken from the lips of a woman.(4)

Judah ben Sirach, who wrote the Book of Sirach, lived during the intertestamental period and expressed strong sentiment against women. He lamented the birth of daughters as a total loss and constant source of potential shame….

“…for moth comes out of clothes and a woman’s spite out of a woman. A man’s spite is preferable to a woman’s kindness; Women give rise to shame and reproach.”

This contempt for women continued into later decades of church history and was held by virtually all the church fathers and many other leaders in the church. It should be noted that while many held views of women as a whole, some held particular women in high esteem. For example, while Jerome did not hold that women could not teach or be in authority, he often sent people to Marcella to settle a question or dispute about the Scriptures. Augustine had great respect for his mother. But the prevalent view of women was extremely negative throughout church history.

“No wickedness comes anywhere near the wickedness of a woman.” Apocrypha, Ecc. 25:19

“Woman was evil from the beginnings, a gate of death, a disciple of the servant, the devil’s accomplice, a fount of deception, a dog start to godly labors, rust corrupting the saints…woman is the head of sin, a weapon of the devil, expulsion from Paradise, mother of guilt, corruption of the ancient law.” Salimbene, a 13th century Franciscan monk

“[A woman] is more carnal than a man, as is clear from her many carnal abominations. And it should be noted that there was a defect in the formation of the first woman, since she was formed from a bent rib , that is a rib of the breast, which is bent as it were in contrary direction of a man. And since through this defect, she is an imperfect animal, she always deceives…” Heinrich Kramer and James Springier, 1486

“Woman in her greatest perfection is made to serve and obey man.” John Knox, 1513-1572AD

“Take up a stick and beat her, not in rage, but out of charity and concern for her soul, so that the beating will rebound to your merit and her good.” Friar Cherubino, 14th century

Martin Luther had much to say about women:

|

| Martin Luther by Lucas Cranach the Elder. Retrieved from Wikipedia |

“Men have broad shoulders and narrow hips, and accordingly they possess intelligence. Women have narrow shoulders and broad hips. Women ought to stay home; the way they were created indicates this, for they have broad hips and a wide fundament to sit upon, keep house and bear and raise children.”

“Women must neither begin nor complete anything without man: where he is, there she must beta nd bend before him as before a master, whom she shall fear and to whom she shall be subject and obedient.”

“Women are ashamed to admit this, but Scripture and life reveal that only one woman in thousands has been endowed with the God-given aptitude to live in chastity and virginity. A woman is not fully the master of herself. God fashioned her body so that she should be with a man, to have and to rear children…”

Luther was so convinced that women are to bear children that he considered the loss of life in childbirth to be no great loss at all since women have no function in life other than to have babies. “If women get tired and die of [child]bearing, there is no harm in that; let them die as long as they bear; they are made for that.”

|

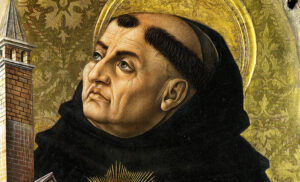

| St. Thomas Aquinas by Carlo Crivelli(c. 1435-1495) |

Thomas Aquinas, arguably one of the greatest theologians the church has known, completely infused the deprecation of women into Christian theology.

“The woman is subject to the man, on account of the weakness of her nature, both of mind and of body… Woman is in subjection according to the law of nature, but a slave is not. Children ought to love their father more than their mother.”

“Woman is defective and misbegotten, for the active power in the male seed tends to the production of a perfect likeness in the masculine sex; while the production of woman comes from defect in the active force.“

He believed that the only help a woman is to a man is in bearing children; in any other capacity, a man would be a more efficient helper. In fact, if it weren’t for the fact that God must have some reason for women,

“the birth of a woman would be just another accident, such as that of other monsters.”

He argued that while both men and women are in the image of God in possessing a natural aptitude for understanding and loving God, only the male “actually or habitually knows and loves God” not the female,

“for man is the beginning and end of woman, just as God is the beginning and end of every creature.”

Aquinas had a low view of sex, believing sexual intercourse to be sin when it is the source of “vehement delight” for the man, causing him to become more like the beasts than any other moment in his life. In other words, according to Aquinas, not war or violence, but joyful sexual union between a man and his wife, is the most beastlike activity of a man.

If these were the views of modern translators, leaders, and theologians, I would imagine many of us would be slow to accept their interpretations. If we listened to a speaker say the things of the nature listed above, we would likely reject their words out of concern they may be influenced by such a strong negative bias. There are some today who reject the gender-neutral translations out of concern of a negative influence of secular feminism, yet we are willing to base our understanding of what the Bible says of women in the church on the precedent set by men with such heinous views of women. These are the men who have had inestimable influence in the translations we currently read, and establishing the church tradition we look to for our practice.

The nature of the Scripture and the nature of those who have read, translated, interpreted, and applied it through the centuries demands that we go back to the original…the words and their contemporary understandings and their historical and cultural context…as much as we are able, if we want to understand what was being said or written and not what’s been interpreted through another cultural lens. It is not an attempt to change passages we don’t agree with but to return to their original meaning. It’s not a rejection of orthodoxy but a return to apostolic orthodoxy. It’s an attempt to peel off the layers of historical cultural bias and resultant teachings, and return to the original words and intentions of the authors as best we are able.

Realizing the need to understand the historical and cultural context of the Scriptures does not mean we all need to be biblical scholars if we want to learn from the Bible or to understand what God is revealing to us personally through the Bible. God does speak to us privately through His word for personal edification and application. Studying the original language and culture adds a dimension to our personal understanding that cannot be overstated but it is not required to be led by the Holy Spirit through the written Word of God.

But when we desire to move beyond personal application to corporate teaching, we carry a heavier responsibility to be sure what we say it means is what it meant to the original audience, especially if we use our understanding to restrict other believers or determine what is biblical or acceptable practice. Establishing doctrine or teaching the Word requires intentionally setting aside for a moment past understanding, and…as we study the historical and cultural context, and the original language…allowing the Bible to speak for itself. We can, and should, look at church tradition, but be mindful of their biases not just our own.

“God spoke to me through His Word” or “The Bible says….” are two different approaches to the Bible; both must depend on Holy Spirit but one requires studying the culture and language in which the Bible was written. We cannot reject scholarly study because it contradicts what we’ve always been taught. Changes in interpretation and understanding that are born from such study cannot be mistaken as capitulation to our modern culture but an attempt to return to the original understanding of the words of God written by the various authors of the Bible.

Endnotes:

1. Fee, Gordon D. 2003. How to Read the Bible for All Its Worth. (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan), p. 21.

2. Bailey, Kenneth E. 1992. Finding the Lost Cultural Keys to Luke 15. (St. Louis, MO: Concordia Publishing House), pp. 143-146.

3. Bushnell, Katherine C. 1943. God’s Word to Women, p. 16. PDF version, retrieved from https://godswordtowomen.files.wordpress.com/2010/10/gods_word_to_women1.pdf

4. Bailey, Kenneth E. 2008. Jesus Through Middle Eastern Eyes. (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press), p. 190.